Capitol Corner

Success or Failure at the IRS: What Will Make the Difference?

For the first time, Congress has provided substantial long-term funding for the IRS. The unprecedented rebuilding program, which includes $80 billion of IRS funding over 10 years under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA, P.L. 117- 169),i provides a once-in-a-century opportunity to restore a depleted IRS. It also presents serious risks for the Biden administration and the U.S. tax system if it fails.

For the first time, Congress has provided substantial long-term funding for the IRS. The unprecedented rebuilding program, which includes $80 billion of IRS funding over 10 years under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA, P.L. 117- 169),i provides a once-in-a-century opportunity to restore a depleted IRS. It also presents serious risks for the Biden administration and the U.S. tax system if it fails.

What will make the difference between success and failure?

Appointing a Qualified Commissioner

To achieve success, the IRS needs a highly qualified, Senate-confirmed commissioner to lead it. The administration has taken the first step by nominating Daniel Werfel —an accomplished and experienced executive. It is critical for Congress to confirm him this year so that he can take the helm as well as ownership of the rebuilding program that Congress has funded. Until this position is filled, the entire rebuilding program is at serious risk of failure.

Congress has long recognized that implementing major change at the IRS requires a commissioner who can make hard management decisions. In 1998 it specified that the IRS commissioner appointment “shall be made from individuals who, among other qualifications, have a demonstrated ability in management.”ii Congress also recognized that it takes time to make important changes and therefore provided a five-year term for the commissioner.iii Now it is important for the Senate to deliver what Congress itself demanded — a qualified commissioner confirmed for a five-year

term.

Increasing Performance

When the new commissioner is in place, his major challenge will be improving the IRS’s performance.

Congress has provided funds — and in a narrow accounting sense, the IRS has to say how it will spend the money. But that accounting exercise is not a

strategy for making investments that will enhance operations. Only clear, regular improvements in the performance of the agency’s mission will allow the new commissioner to win the confidence of the public and Congress. Money alone will not make that happen.

The risk is that the IRS will just do a little bit more of everything it is doing today. But that will not work, because despite many misleading statements

about massive increases in the size of the agency, the new funding (even after 10 years) will bring the IRS to only about 75 percent of its size relative to the economy that it was in the 1990s.iv

Since I was the commissioner, I know that even then, the IRS’s service to the public was inadequate, and the tax gap (taxes owed but not paid) was too big and growing.

Unless performance improves markedly, the IRS could end up 10 years from now having spent a lot of money to accomplish only marginally more. And without clear progress along the way, the rebuilding program will likely be declared a failure before the 10 years is up.

To realize the results that Congress and the public expect from the increased funding, strong and consistent leadership will be essential to making and executing complex decisions in five key areas:

- setting strategic performance goals;

- setting rigorous priorities;

- organizing for results;

- defining and implementing effective

- compliance strategies; and

- communicating effectively with external and internal stakeholders.

Setting Strategic Performance Goals

Strategic performance goals are a statement of how the IRS will improve the way it serves all taxpayers.

These goals should be carefully and clearly defined to guide action that leads to measurable progress in the IRS’s mission. The two essential strategic

performance goals for the agency are (1) service: making every taxpayer interaction a high-quality, efficient one; and (2) compliance: increasing voluntary and enforced compliance to reduce the tax gap.

The IRS has a lengthy list of responsibilities and activities, such as protecting taxpayer data, hiring and training a diverse and competent workforce, and accounting for large sums of money from millions of taxpayers. Performing these activities should be thought of as the minimum required table stakes. They must be done, but they are not what drives the agency forward.

All interactions with taxpayers should be high quality and efficient, both in content and delivery method. The service goal should therefore include improving all forms of taxpayer interaction, not just routine inquiries such as when a refund will be paid or how to fill out a tax form.

The IRS receives separate appropriations for service and enforcement. Many taxpayer interactions (and some of the most important) occur as part of activities such as audits and collections that are funded by the enforcement appropriation. The IRS has approximately 677 million interactions with taxpayers every year through various channels, including correspondence, phone calls, and online transactions. About 175 million of these interactions are outbound notices from the IRS, many of which are part of an IRS enforcement program.v

In her report to Congress for 2018, National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson noted, “The IRS mailed over 175 million notices in fiscal year (FY) 2018, making notices one of the most frequent interactions between taxpayers and the IRS.”vi In many cases, notices are the primary form of communication from the IRS to taxpayers concerning matters that have a significant effect on taxpayers’ lives. The report also said, “In the three Most Serious Problems that follow, the National Taxpayer Advocate expresses concerns about IRS notices that fail to adequately inform taxpayers about their rights, responsibilities, and procedural requirements.”vii The report recommended that the IRS use research to redesign its reports to be more understandable and useful to taxpayers. As of this writing, none of these recommendations have been implemented.viii

The goal for improving all taxpayer interactions will require completely rewriting the content of notices to be clearer and more modern, with highly specific explanations of issues concerning taxpayer returns and data, and with links to references and accounts when appropriate.

These communications should provide taxpayers with a range of options for responding to the IRS, including the use of self-service accounts and secure online communications.

The compliance goal should be to reduce the tax gap by using a range of methods, many of which depend on the use of data and technology. Enforcement itself is not a goal, but it is one tool for achieving compliance.

This way of thinking is critical because just scaling up traditional audits will be inadequate. Even doubling the return from audits would reduce the tax gap over 10 years by less than 2 percent. That is 80 percent less than even the conservative estimates made by the Congressional Budget Office.ix

A key part of setting performance goals is to establish meaningful ways of measuring actual progress. What is not measured will almost never get done, and faulty measures can cause not only waste but real damage.

Congress recognized the importance of setting and measuring performance goals by twice passing the Government Performance and Results Act, most recently in 2010. Unfortunately, it is all too easy for this requirement to become merely a formal exercise, or to go awry and drive counterproductive behavior, as it did in the mid1990s when inappropriate enforcement goals were rolled out for the IRS.x

Serious work needs to be done in the IRS to develop indicators of actual progress for improving service in all taxpayer interactions and meaningfully reducing the tax gap.

The key guideline is to develop measures that are roughly right rather than precise but wrong, meaning that they indicate actual progress toward strategic performance goals even if they measure only partial results or do so imperfectly. By contrast, spending money and tracking activities like the

number of audits are not adequate ways to measure progress on strategic goals.

As examples, measures of progress on the quality of taxpayer interactions can include traditional ones, such as telephone answering, but should also

include measures of the results of those interactions, like whether a question was answered correctly or a problem was resolved. Answering a phone call in 10 seconds is good but not if it provides no useful answer to the taxpayer’s question. Taxpayer feedback through short surveys is essential.

General measures of compliance should be done more frequently than in past compliance studies, the latest one of which was just issued for the years 2013-2016. In the interim, more frequent metrics on trends in key areas of noncompliance, such as for particular sources and kinds of business income, should be developed. In compliance reporting, indicators of trends in areas of noncompliance are more important than absolute metrics.xi

Setting Rigorous Priorities

The IRS needs to set rigorous priorities for action programs that clearly and timely make progress toward the performance goals, integrating technology into almost every program.

Making progress toward goals requires careful planning to break down long-term goals into practical projects that can be implemented and evaluated in reasonable periods, usually measured in months rather than years. Defining priorities requires strong leadership to allocate limited staff and financial resources to achieve the best results while managing risk. In the absence of rigorous decision-making, too many projects are likely to be approved, diluting resources and management attention and resulting in delays or outright failures. Still another risk is that projects will be defined too broadly with long time frames for implementation.

For example, projects already underway to improve taxpayer interaction include callbacks, secure electronic access to taxpayer accounts, self-service account updates for specified items (even including installment agreements), and secure electronic communication between IRS employees, taxpayers, and practitioners — all of which depend on technology. The technology to accomplish these initiatives is widely available but deploying them effectively at the IRS is a complex endeavor that includes training agency employees and communicating effectively with the public.

The elimination of most remaining paper filings is an essential part of improving the taxpayer experience as well as increasing efficiency at the IRS. Several techniques are available and have been recommended repeatedly over time, such as requiring barcoding on returns produced on computers and submitted on paper. This recommendation was first proposed by the national taxpayer advocate in 2004.xii

The plan to accomplish this goal needs to incorporate available technology; include regulatory considerations; provide for consultation with taxpayers, practitioners, and tax software providers; and be implemented in well-defined steps.xiii

Organizing for Results

The IRS needs to make clear assignments of responsibility for the execution of priority programs.

At the top level, a governance process needs to be established that can make timely, firm decisions on a host of issues. This includes conflicts in priorities, competition for resources, and technical, procedural, or regulatory problems that always arise in the execution of change programs. Vetting

important decisions with input from all key parts of the IRS will lessen the risk of major and expensive setbacks, such as those that recently occurred in the IRS’s well-intentioned but flawed implementation of a project to provide more secure taxpayer online identification.xiv

Effective governance of the IRS rebuilding program will also require difficult decisions to adjust or even cancel initiatives that may not be achieving their goals. No major improvement program achieves success in every initiative, and it is normal and necessary to make those adjustments.

Improving performance also means changing long-established ways of doing business. Key leadership positions will have to be filled with individuals from inside and outside the IRS who are committed to improving the way the agency operates its core service and enforcement activities to reach performance goals. I believe that it is possible to recruit highly talented individuals for the IRS by stressing the unique opportunity that exists to rebuild one of the foundations of the American government — our tax administration system.

In most cases, the work to implement priority programs should be done by integrated teams that include legal, tax, data science, technology, and communication experts, all led by an empowered executive. They should usually include individuals with frontline experience who can provide a practical perspective on how the changes will work in the field.

IRS technology management will have to develop plans for executing longer-term technology renewal projects, such as the replacement of IRS master files. This decades long technology effort should not and need not impede near-term business improvement projects that also depend on deploying technology. Almost all large organizations have the problem of old but essential legacy systems that need to be replaced over time, but they do not and cannot allow them to undermine progress on necessary business improvements.xv

Effective Compliance Strategies

The IRS needs to define and implement compliance strategies that make far better use of data and technology to drive and support more productive

enforcement actions and encourage voluntary compliance.

The tax gap has grown to over $600 billion per year. If nothing further is done, this loss will accumulate to more than $7 trillion over 10 years — considerably more than all the income taxes paid by 90 percent of all individual taxpayers.xvi About $140 billion per year of this lost tax revenue is from underreporting by passthrough businesses at the entity level, most of which is not even included in past IRS estimates of the tax gap.xvii

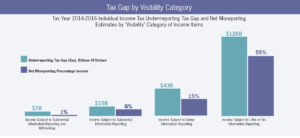

The reason for the continued growth in the biggest part of the tax gap is the lack of progress on income that is only reported on the tax return itself and not separately verified by third parties such as employers or payers. When the IRS has third-party data and uses that data effectively, the compliance rate is 94 to 99 percent. When it has no data, or has data but does not use it effectively, the rate is just over 50 percent, as shown in the figure, taken from the most recent IRS compliance study. These rates have not significantly changed in decades. The dollars lost just grow larger as the economy expands.xviii

The lack of progress in addressing the biggest and most lopsided part of the tax gap is extremely unfair to the vast majority of taxpayers who are paying all of what they owe.

The large amount of lost revenue is heavily concentrated among upper-income taxpayers.

By our estimate, at least half of the entire tax gap is attributable to underreporting by taxpayers reporting incomes over $160,000 (the top 10 percent of taxpayers), and at least 35 percent is from those reporting incomes over $400,000.xix

Today the IRS’s main tool for addressing the large segment of lost tax on underreported income that has limited third-party reporting is traditional audits, which are too few and too inefficient to have much effect. All of the IRS’s audits collectively recover only about $10.5 billion per year, less than 2 percent of the tax gap. The auditing of passthrough businesses is negligible — about 0.06 percent or six audits out of 100,000 returns. xx

Because of the relatively modest revenue recovered through audits, there is scant evidence that they have much of a deterrent effect either, especially on upper-income taxpayers.xxi

The inefficiency of the IRS’s approach to audits also imposes an unnecessary burden on compliant taxpayers because 21 to 73 percent of audits are “no

change” audits, which means they did not need to be done at all.xxii The fraction of unnecessary audits would be even larger if those that recovered some tax, although an immaterial amount, were included in the data.

For the IRS to make progress on reducing the tax gap, new strategies that make much more use of data and technology will have to be applied on a larger scale. The IRS has had significant success in limited sectors with this approach — for example, in the Return Review Program that screens for

inappropriate refunds and in parts of the Criminal Investigation division.xxiii

But the IRS has enormous amounts of data that it is not using and many more opportunities for new compliance approaches. In total, the IRS receives

about two billion information reports per year from payers and employers who report a total of almost $18 trillion of income (yes, trillions).xxiv Only a fraction of this information is used in systematic, automated processes by the IRS.

Here are some examples of more efficient compliance strategies.

The IRS receives approximately 30 million Schedule K-1 (Form 1065), “Partner’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc.,” returns reporting over $1.2 trillion of income from passthroughs but makes no systematic use of this data unless an agent uses it in an audit.xxv With current technology, these returns could all be analyzed to identify and follow up on discrepancies.xxvi

In May 2020 the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration reported that high-income nonfilers owing billions of dollars in taxes were not being examined. The report noted that the IRS has the information necessary to identify these nonfilers from employers’ Forms W-2, taxpayers’ Forms 1099, and related and prior tax returns.xxvii

Similarly, in December 2020 TIGTA reported that billions of dollars in potential taxes were missed from taxpayers that received income reported on Form 1099-K, “Payment Card and Third Party Network Transactions.”xxviii The report also noted that “numerous business and individual taxpayers with reporting discrepancies of at least $10,000 between the reported Tax Year 2017 income on the return and the Form 1099-K income were not identified by the IRS’s underreporter programs, or were identified, but not worked.”xxix

Separately, a study showed that just one small subsegment of business income — short-term rental income — likely accounts for $2 billion of unreported tax and is now reported on Form 1099-K but is not used by the IRS in any automated method.xxx

The Government Accountability Office performed an extensive study in 2007 of underreported tax by sole proprietors, which are business owners that report their income directly on their individual tax returns. The GAO reported that 28 percent of the entire tax gap was caused by underreporting in this category of income and that 10 percent of the sole proprietor returns accounted for 61 percent of the underreported tax.xxxi In this and other studies, the GAO identified 22 options for addressing this part of the tax gap, but in a follow-up project, GAO said, “As of May 2021, Treasury has taken no action to address this recommendation and has not provided GAO with plans to do so.”xxxii

Similar strategies must be developed and implemented for the huge and growing passthrough sector. Businesses in the passthrough sector now report

total positive income exceeding $1 trillion, rivaling that of all corporations. Our independent estimate is that this passthrough sector accounts for approximately $140 billion per year of tax on underreported income at the business entity level, almost none of which is recovered by the IRS.

Also, new strategies will be required to address the tax lost by the underreporting of income from new parts of the economy, such as cryptocurrency transactions, which are not covered by official tax gap estimates since they barely existed when IRS compliance studies were done.

To make meaningful progress on reducing the tax gap and doing so efficiently, the IRS must transform its entire compliance approach to one that is driven by data and technology, supplemented by skilled and effective enforcement teams. Available data combined with machine-learning technology can vastly improve the efficiency of enforcement activity if used properly.xxxiii

The next IRS commissioner would be well served by setting up a small compliance strategy office, led and staffed by highly qualified experts in data science, statistical analysis, tax law, auditing, and technology, recruited from inside and outside the IRS. All these disciplines, including auditing, are widely applied in the private sector as well as the IRS, and there is much to be learned from them. xxxiv

The IRS operating divisions, such as Large Business and International and Small Business/ Self-Employed, can execute a more effective strategy if

provided with effective guidance, data, and tools.

As with all the major change programs in the IRS, the implementation of a modern compliance strategy will have to be led by an empowered and

effective governance process with the commissioner as the ultimate decisionmaker.

Communicating Effectively

The IRS deals directly with almost every family, business, and nonprofit entity in the United States — more than any other institution — and has a significant effect on those it serves. It is therefore appropriate that the agency be subject to substantial oversight. To this end, eight congressional committees have oversight jurisdiction over the IRS. They are supported by the GAO in the legislative branch and TIGTA. Together these bodies issue hundreds of reports on the IRS each year and investigate any suspected incidents of wrongdoing.

The Treasury Department is the IRS’s parent agency and has responsibility for critical matters that greatly affect its performance, including approving

budgets and issuing regulations and other forms of tax guidance. Close alignment with Treasury is essential.

Private sector groups consisting of practitioners, accountants, and lawyers regularly meet with and comment on the IRS, and they are the subject of continuous coverage by both specialized tax publications and general interest media.

The IRS Oversight Board, which was established by Congress to provide independent private sector expertise and advice to the commissioner, has

not been functioning because of a lack of appointees. A reconstituted board could provide valuable, forward-looking advice on matters such as resource allocation, internal organization and recruiting, strategic planning, technology management, and communications, which other auditing and oversight bodies generally do not provide.

Internally, the IRS employs more than 75,000 people who are spread across the United States, as well as many supporting contractors, all of whom

must be motivated and trained to accomplish the agency’s mission.xxxv

Communicating with these many stakeholders is a major job of the IRS commissioner. In my five-year term, I testified 48 times in congressional hearings and traveled almost every week to meet with employees and outside groups.

Honest, accurate, and meaningful communication in all these settings is essential to building credibility — internally and externally. Equally important is establishing reasonable expectations and realistically acknowledging challenges, risks, and setbacks — all of which inevitably occur.

These challenges will only increase because of the long-term funding now available to the IRS. This funding will increase expectations for improved IRS performance since it can no longer be cited as a major constraint.

The Bottom Line: Success or Failure

With the passage of long-term funding for the IRS, Congress has provided an opportunity for the federal government to rebuild one part of America’s

critical infrastructure — our system for administering a tax system that accounts for approximately 20 percent of the economy and touches nearly every family, business, and institution. This system has been in decline for most of the past 25 years and is badly in need of transformation to one that

taxpayers believe is fair and effective in the 21st century. The opportunity now exists to accomplish this vital goal, but it will require exceptional leadership and constructive forward-looking oversight to happen. If this opportunity is not seized and acted upon successfully, another chance will not soon occur, and the risk to the tax system will only increase.

This article is reprinted from Tax Notes Federal, December 19, 2022, p. 1661 with permission of Tax Analysts. Copyright 2022 Charles O. Rossotti. All rights reserved.

i IRA, Title I, Subtitle A, Part 3.

ii IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998.

iii Id. at Title I, subtitle B.

iv Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG IRA Exhibit 1: IRS Resources Relative to Economy” (Nov. 10, 2022).

v Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG IRA Exhibit 2: Taxpayer Interactions by Type” (Nov. 10, 2022).

vi National Taxpayer Advocate, “Annual Report to Congress 2018,” at 170 (Feb. 2019).

vi Id. at 198.

viii Id. at 195.

ix Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG IRA Exhibit 4: Enforcement Revenue From Auditing” (Nov. 10, 2022).

x Charles O. Rossotti, Many Unhappy Returns: One Man’s Quest to Turn Around the Most Unpopular Organization in America 109 (2005).

xi For a more complete discussion of IRS metrics, see Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG Goals, Metrics, Taxpayer Rights & Oversight” (Mar. 24, 2021).

xii Olson, “How Did We Get Here? 2-D Barcoding and the Paper Return Backlog — A Missed Opportunity,” Procedurally Taxing, Feb. 24, 2022.

xiii For a more complete discussion of how technology can be used to improve all forms of service to taxpayers, see Fred Forman and Rossotti, “The Business Case for IRS Transformation,” Shrink the Tax Gap ebook (Sept. 2021).

xiv Michelle Singletary, “Despite Privacy Concerns, ID.me Nearly Doubled the Number of People Able to Create an IRS Account,” The Washington Post, Feb. 25, 2022.

xv For more discussion on how IRS improvement programs can be organized, see Rossotti and Forman, “Recover $1.6 Trillion, Modernize Compliance and Assistance: The How-To,” Tax Notes Federal, Sept. 14, 2020, p. 1961.

xvi Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG IRA Exhibit 3: Tax Gap Update” (Nov. 10, 2022) (Shrink the Tax Gap projected forward the estimates for the latest IRS compliance study, which covered years 2017-2019. Our estimate includes an estimate for taxes on underreported income at the passthrough business entity level, which are not included, except incidentally, in the IRS study.).

xvii Shrink the Tax Gap, “Appendix A: Methodology for Calculating Tax Gap From Underreporting of Passthrough Business Entities” (Oct. 28, 2022); and Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG IRA Exhibit 5: Tax Gap From Underreported Income by AGI” (Nov. 10, 2022).

xviii IRS, “Federal Tax Compliance Research: Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2014-2016,” Pub. 1415 (Oct. 2019).

xix Shrink the Tax Gap, “STTG IRA Exhibit 5,” supra note 17 (IRS statistics report distribution of income and tax paid classified by the amount reported by the taxpayer, so taxpayers who underreport are shown in a lower bracket. For example, a taxpayer reporting income of $190,000 who underreports by 55 percent (which is the average underreporting percentage for low-visibility income) actually has income of $422,000. Further, our estimates only account for underreporting of income tax, and do not include related underreporting of employment taxes.).

xx Shrink the Tax Gap, supra note 9.

xxi Phill Swagel, “The Effects of Increased Funding for the IRS,” Congressional Budget Office Blog, Sept. 2, 2021.

xxii Shrink the Tax Gap, supra note 9.

xxiii Shrink the Tax Gap, “Appendix G: STTG Technology Paper Case Studies” (Aug. 18, 2021).

xxiv Shrink the Tax Gap, “STGG IRA Exhibit 6: Information Returns Filed for Calendar Year 2019” (Nov. 11, 2022).

xxv Id.

xxvi Forman and Rossotti, supra note 13.

xxvii TIGTA, “High-Income Nonfilers Owing Billions of Dollars Are Not Being Worked by the Internal Revenue Service” (May 29, 2020).

xxviii TIGTA, “Billions in Potential Taxes Went Unaddressed From Unfiled Returns and Underreported Income by Taxpayers That Received Form 1099-K Income” (Dec. 30, 2020).

xxix Id.

xxx Forman and Rossotti, supra note 13.

xxxi GAO, “Tax Gap: A Strategy for Reducing the Gap Should Include Options for Addressing Sole Proprietor Noncompliance,” GAO-07-1014 (July 2007).

xxxii GAO, “Questionnaire on Policy Options to Improve Sole Proprietor Compliance” (Oct. 7, 2022).

xxxiii For a more complete discussion of how the IRS can use data and technology to address the tax gap more effectively, see Forman and Rossotti, supra note 13.

xxxiv Shrink the Tax Gap, supra note 23.

xxxv IRS Data Book 2021, Table 32.